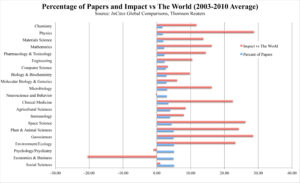

PERIODICALLY Thomson Reuters presents a profile of Australian research across all academic fields. It reports the relative impact of papers with an Australian author versus those published in the rest of the world.

For the period 2003-10 the overwhelming conclusion of this analysis was that the field of economics and business was by far the worst performing sector of Australia’s universities (see graph).

For the period 2003-10 the overwhelming conclusion of this analysis was that the field of economics and business was by far the worst performing sector of Australia’s universities (see graph).

As a now retired senior member of this research community I was embarrassed, but not totally surprised by the assessment.

One of the primary roles of the first Excellence in Research in Australia review was to assess research excellence in an international context. Given the Thomson Reuters review my expectations were that this assessment would reflect this sorry state of affairs.

It did not. In the field of commerce and management my old university received a top rating, as did one other institution. The top rating supposedly reflects “outstanding performance well above world standard”.

As one of the associate deans responsible for research I knew we were locally very good, but as a group, certainly not well above world standard. This is the province of places like Harvard, Stanford and MIT. Our problem was that we had a small number of world-class individuals but too many under-performing researchers.

How did ERA I signal that Australia had two excellent faculties of commerce and management? A panel ranked a portfolio of research from each university. It then gave the top groups the top rating. What it did not do, and what the Thomson Reuters assessment did, was to directly benchmark against other international scholars in their discipline.

For some reason, the ERA panel did not use citation data as one of its key metrics. Nor did it select some comparable overseas institutions as benchmarks. These two approaches would have highlighted the international standing of our scholars, their research, and the quality of various faculties relative to a clearly stated group of peers.

Such a measurement scheme would also reflect the fact that, in most cases scholars operate in an international market for their ideas. In essence, research excellence is an international metric.

Will ERA II produce a more valid assessment of our research excellence? In my opinion, certainly not. There are three reasons for my belief. First, the discipline areas will be once again only ranked local-for-local. Under these circumstances, it will be politically incorrect, if not impossible, not to have a least one institution rated as “world class”.

Second, the criteria that produce this ranking, namely, the subjective evaluation of a panel will not be transparent, and hence it will be impossible to reverse engineer their evaluations. Hence, those faculties that need to improve will not know precisely what to do prior to the next evaluation.

Although the old list of journal rankings that was used as a key metric of research quality was contested by some scholars, it was transparent and in line with international scholarly norms. It was also democratic in the sense that the final list reflected the judgment of peers (via citations and journal impact factors), and it was circulated to, and amended by Australian academics before it was used by the panel members of ERA I.

Finally, I do not understand the criteria used to select the panel members. If you are going to disregard citations and replace a public and democratically created list of journal rankings with the opinion of a group of assessors, then you place a heave burden on the panel to do a good job.

This group needs to broadly represent the sub-disciplines of economics and commerce, and it needs to have a demonstrated, current capability to assess research quality in the international marketplace. These criteria will provide the panel with the moral authority to justify their judgements.

There are two well-respected cadres of people who automatically fulfil these requirements. One group is the top scholars in each sub-discipline. In each sub-discipline there is a small group of people whose scholarly impact is accepted by their colleagues as world class.

A second sub-group is the scholars currently on the review boards of the top international journals. For example, when I selected the top 50 business management journals by 2011 impact factor, plus the others from the Financial Times list of journals, and a further 3 that had influence factors greater than 1, I could identify 127 Australians who are currently on one such journal review board and 27 who were on two boards.

In the field of economics a similar selection process across 32 economics journals identified a further 25 people. Of this highly influential group of scholars only 3 are on the economics and commerce review panel.

Because research quality has different interpretations across disciplines, a particular shortcoming of the ERA II panel is the spread of sub-discipline areas represented. The profiles of the 16 panel members suggest that marketing and economics with 4 and 5 members each are over-represented.

Also, missing is recognised expertise in some established and significantly rising areas of business and management scholarship, such as international business and management, business strategy, operations and supply chain management, transportation, tourism, corporate governance, innovation and entrepreneurship, and business ethics.

What is the likely outcome of the current research evaluation set up? First, the ERA panel will need to agree on how to formally measure research quality. This can be a difficult task if panel members have different views on the importance of research inputs (such as grants), outputs (such as journal quality – of which there is no longer an agreed metric), and impact (such as citations).

Interestingly, the economics and commerce panel is one of the few groups in the Thomson Reuters graph that will not use citations as a measure of impact.

Because of a lack of transparency of the specific evaluation criteria, universities will likely prepare a more varied set of proposals than before and thus will make the ranking task of the ERA panel harder and more contentious.

In such a circumstance it is highly likely that, except at the extremes, the panel will be unable to make distinctions amongst the different faculties. Also, it is likely that disgruntled faculties will question many of the judgements of the ERA panel which they will then be unable to counter by falling back on objective measures that are verifiable independently.

If there are any serious funding implications of this exercise, either amongst universities or within an institution, we can expect some disruptive arguments.

My prediction is that the next economics and commerce research assessment is unlikely to produce a rigorous evaluation of either the international standing of our research, or its quality relative to our other university disciplines.

And it won’t offer a better understanding to business faculties of how this can be improved. Given that these are two valuable outcomes of the ERA exercise, the current approach seems designed to further entrench the current under-performing culture of scholarship in an area vital to the wellbeing of Australia.

Pingback: Why MOOCs are Good for Australian Business Education and Scholarship