The recent decline of the majority of Australian universities in the World University Rankings has university vice chancellors passing on the blame to the government and the system underlying the rankings. According to Prof Glyn Davis of The University of Melbourne: “… negative media reports overseas of very substantial funding cuts to the sector by the previous government have played out in the reputation indexes dragging down institutions.” While Simon Marginson notes that: “To base a university ranking on opinion surveys is like asking a group of people to guess the distance between the earth and the sun and using the average guess to determine the distance. It wouldn’t be very good astrophysics and it isn’t very good social science of higher education either.” (See article here.)

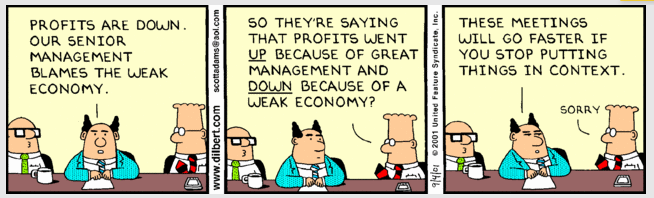

However, behind this discussion lurks a disturbing trend. When doing well senior management are quick to attribute their organisation’s success to “vision and strategy”, while when things don’t turn out so well it is either the “measurement of performance” or some combination of “animal spirits” and “market conditions”. In the case of the universities this invariably leads to calls for more access to other people’s money. For us individual academics the same logic would imply that it is not our failures as scholars that get our papers rejected from journals but the fact that the review process is flawed; after all doesn’t the review process imply some mixture of “opinion” as to what is “good science”? Similarly, I could argue that only thing keeping me or any of my colleagues from getting that early morning call from the Nobel Prize committee is the fact that our salaries and funding are just too small for our superior intelligence to be revealed. If only our universities would give us more salary and funding. I can imagine what my students would say when I give them their marks: “Isn’t this just your (meaning mine) flawed opinion?” or “If my parents just gave me more money then I would have done better”.

This discussion also assumes that it is only the Australian universities that are threatened by real and potential funding cuts (see these articles for discussions on the UK, EU, and USA). There was this little thing called the financial crisis that had significant effects on the funding models of many leading universities in the US and elsewhere via reductions in taxpayer funding, reduced admissions and a drastic downturn in the return to endowments. Yet all during this period, when the funding to Australian universities was remarkably protected in relative terms, our universities did not launch up the rankings.

The point of this discussion is that all organisations, public and private, face funding constraints. That is a simple reality. What matters more at the margin is what choices are made with respect to how the funds that are available are spent. My experience in Australia for 15+ years has been that it is the reaction to the constrained economic conditions, rather than those conditions per se, which has hurt rather than helped the standing of the universities. For example, while many academics have been made redundant (based on “poor” performance), salaries have been constrained, class sizes have increased, support staff for faculty have declined, and we have been asked to pay for more and more out of our own pockets, little constraint and accountability has been placed on the administrative system and managers who will readily attribute good performance to their own leadership.

For example, what really matters to a university’s standing and viability? It is the faculty who teach the students, engage in scholarship, generating grant funding, and build reputation. The management and leadership of the university are generally a cost (since there is little if any real fundraising, which is what takes up a significant proportion of time at leading non-Australian universities, highly paid senior administrators become much more of a burden since each faculty member must carry more of a cost load). Hence the value of university administration (particularly at the top) is not as a primary asset but as an asset that complements the faculty in the production of its revenue and reputation building endeavours. However, what we have seen in Australia is the development of a system where rather than the management being a complement to the faculty, the faculty have become simply a means by which managers meet their key performance indicators. And in many cases these performance metrics are thought up by bureaucrats or panels with little substantive experience in doing quality research or teaching.

What we have seen in Australia is a back to the 1960s centralisation that is removing much of the innovation from the system. It is quite well known by those working on innovation that the more structured and hierarchical the organisational environment is, the less the potential for innovation. It is also well understood that the more autonomy that is given to individuals — i.e., scientists and scholars in the case of universities — the greater the potential for innovation. However, our universities have gone in the opposite direction. Again, the importance of this is seen by the fact that VCs and Presidents, DVCs and Vice-Presidents, Pro-VCs, Deans, Executive Deans, Deputy Deans, Associate Deans, etc. do not generate the key capital that makes a university great. They do not teach the students. They do not make the discoveries. They do not publish the research and scholarship. They do not generate reputation. Their value comes solely by releasing the potential of the faculty.

What then is to be done? It is about time that the management of our universities came to recognise that what makes universities what they are is the collective capabilities of the faculty. Rather than worrying about the government policy or rankings they should be concerned about maximizing and releasing the value of the individuals who are the engines of the university. What this requires is putting the power and decision making authority closer to the outcomes that matter, educating students and producing great scholarship. This only come about when leadership is endowed from below, not granted from above. In this they should listen to Herb Kelleher the entrepreneurial founder and CEO of Southwest Airlines: “If the employees come first, then they’re happy…. A motivated employee treats the customer well. The customer is happy so they keep coming back, which pleases the shareholders. It’s not one of the enduring green mysteries of all time, it is just the way it works.” …

Recent Comments